Smallholder women farmers in Jigawa State are facing obstacles in accessing markets and achieving economic empowerment. Despite promises made in the national policy on gender in agriculture to improve market access and value chain development, these women continue to struggle due to lack of empowerment and infrastructure.

Ramatu Dahiru is a smallholder farmer in Dutse, the capital of Jigawa State. Besides her investments in livestock and home-based irrigation farming, Dahiru annually cultivates acres of land around the state capital, growing millet, sorghum, groundnut, beans, and other cash crops.

Last year, she faced a significant farming crisis due to encroachment on her land.

“My neighbour felt that because I am a woman and there’s nothing I can do about it, he simply encroached on parts of my land by farming there, thus extending his own into mine unfairly,” Dahiru said as she took this reporter around her farm.

She was the only woman farmer among all the male farmers in the area.

As the rainy season began, marking the start of the farming season, Dahiru worried about a possible recurrence of the same issue. The previous conflict took various interventions to settle and delayed her cultivation.

Dahiru explained that the delay in accessing her farmland frustrated her efforts to earn income from her produce. She noted that although she had previously sought intervention from community leaders, she still faced the challenge of encroachment on her farmland, which she partly attributed to her gender as a woman farming in an area traditionally dominated by men.

Her experience points to a broader pattern of gender-based discrimination and barriers that women farmers like her face in accessing and retaining control over their land and agricultural resources.

Section 1.3, sub section 5 of the National Policy on Gender in Agriculture condemns all forms of gender-based violence in the agricultural sector. It recognises the need to address and eliminate violence against women in agriculture, ensuring a safe and conducive environment for their participation.

However, there are no clear indications of how this policy is being enforced, especially for women like Dahiru who say that only the intervention of community leaders has had some effect in addressing the persistent challenge they face.

Without a reliable source of produce due to the unauthorised takeover of their farmland, women farmers’ access to markets, which is crucial for selling their crops at competitive prices, generating steady income, and reinvesting in their farms, remains severely constrained.

As the national policy on gender in agriculture states, gender equality is essential for the sustainable development of the agricultural sector. Yet, the experiences of women farmers like Dahiru suggest that gaps remain in translating the policy’s commitments into tangible outcomes and protections on the ground.

Even when Dahiru and other women farmers like her manage to harvest farm produce, other barriers such as lack of transportation, storage facilities, and market information systems greatly hamper their ability to efficiently transport and store their produce.

“To move our produce to the market, we rely on donkeys but it is time-consuming,” Dahiru quipped.

Such infrastructural deficiencies not only limit their market access but also hinder their participation in value-added activities such as processing and marketing, which could significantly increase their income and overall economic opportunities.

“We do not have dedicated places where we can keep our crops safely after they are harvested especially our perishable crops, like fruits and vegetables, that will spoil quickly if not stored properly.

“Without good storage, we have to sell our crops right after harvest, even if the prices are low, because we have nowhere to keep them,” Dahiru explained.

This is worsened by a much wider gap where women farmers constantly face exploitation in negotiations and limited access to crucial resources.

According to findings by this reporter, women farmers lack the necessary negotiation skills to secure fair prices for their crops. This leaves them vulnerable to buyers who may take advantage, offering significantly less than the market value.

The situation is further complicated by a lack of access to legal representation when faced with land disputes, such as encroachment or seizure; women farmers have limited options for resolving such conflicts. Yet, section 1.4 national gender policy emphasises the need for gender-responsive programming, including legal support for women in agriculture.

Furthermore, the unequal distribution of resources is a lingering one. Government support programs, like fertilizer distribution and mechanized farming equipment, often prioritise men, leaving women with insufficient supplies to meet their agricultural needs.

Dahiru, an active member of the Small-Scale Women Farmers Organisation in Nigeria (SWOFON), emphasises the gender disparity in resource allocation.

“For example, they (the government) can give only 10 bags of fertilizer to over 100 women to share. How can it be adequate?” she questioned.

This limited access to resources, coupled with the lack of negotiation skills and legal protection, creates a situation where women farmers are disproportionately burdened. The gender policy calls for equitable access to resources and opportunities, ensuring that both men and women can achieve their potential and sustain suitable livelihoods (Section 1.3).

For Sadiya Adamu, another smallholder farmer in Kafin Gana, Birnin Kudu LGA, lacking storage facilities and wanting to earn more money means she has to pound some of her farm produce by hand to process it.

“Here in Kafin Gana, the work never seems to end; I cannot continue pounding and hitting by hand every day. It’s a constant worry. How much longer can I keep this up before it’s too much?” she quizzed.

Typically, Adamu pounds staple crops such as millet or sorghum, spending an average of 4-6 hours a day to pound and package it. Depending on the quality and quantity of the produce, she might realise between N5,000 and N10,000 per week.

While pounding is not the only way to process these crops – alternatives like grain mills or motorized decorticators exist. However, Adamu’s lack of access to such machinery limits her productivity and takes a toll on her health.

With the aid of better machinery, Adamu says she could potentially earn between N20,000 and N50,000 per week, and she would also have more time to focus on other aspects of her personal life.

Again section 1.4 of the policy advocates for gender-responsive delivery of agricultural services, including access to appropriate technologies and equipment.

Sharing in Adamu’s challenge, Halima Baso, another smallholder farmer in Baso – Kiyawa local government area, lamented the absence of proper storage facilities which is another major hurdle faced by women farmers.

“The lack of silos forces us to sell our harvest right after reaping, even if the market price is low. We have no choice; our crops will spoil if we can’t store them properly,” Baso said.

This pressure to sell quickly puts women farmers at a disadvantage, as they have less bargaining power and are forced to accept lower prices.

With respect to the gender gap in market access, Baso says many men in these communities are able to participate in a barter system, exchanging their crops for other necessities. However, this option is often unavailable to women.

As Baso points out, “The men take their crops to the market and trade them for things we need, like cooking oil or fabric. But for us, it’s just cash. We have to pay the high transport costs, which eats into our profits,” she explained.

These high transportation costs stem from the rising price of petrol, forcing many farmers to rely on donkeys to transport their goods. This not only adds significant time to the journey but also damages the quality of the produce.

“The donkeys can only carry so little,” says Hajiya Hadiza Giwa, the Jigawa State Coordinator of SWOFON.

“By the time we reach the market, our fruits and vegetables are bruised and wilted. It’s frustrating, because we know we could get a better price if they were still fresh,” Giwa emphasised.

She, however, said that in recent times, there has been improvement in supporting women farmers in the state by the government, particularly through programs like NGCares, calling on the government to do more.

Agricultural Interventions in Jigawa State

The NG-Cares initiative in Jigawa State is part of the Nigerian COVID-19 Action Recovery and Economic Stimulus programme which aims to support the recovery of the state’s agricultural sector from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The programme’s objectives include empowering young people to engage in agriculture, producing high-quality rice seeds, creating jobs, providing training, inputs, and market linkages to farmers.

Some of the programme’s achievements, according to a statement published on the NG-Cares Initiative website, include 10,730 vulnerable households receiving agricultural inputs, 4,220 beneficiaries being selected to receive inputs and agricultural assets, 2,000 beneficiaries receiving seeds, fertilizers, and crop production chemicals, and 2,220 beneficiaries receiving critical farm assets like water pumps and processing machines.

However, the gender balance in the distribution to beneficiaries remains unclear.

Agricultural experts speak

In a telephone interview, Umar Gambo, a retired agricultural extension worker at the Jigawa Agricultural and Rural Development Authority (JARDA) and now an Agric Officer with Agro-

Climatic Resilience in Semi-Arid Landscapes (ACReSAL), a World Bank assisted Project aimed

at addressing the challenges of land degradation and climate Change in Northern Nigeria on a

multi-dimensional scale, attributed some of the challenges faced by women farmers to religious and cultural attachments. He noted that these are powerful forces influencing human behavior, particularly in regions in the north, where the mingling of women and men is discouraged.

This deeply entrenched norm makes it difficult for women to go to the market and interact with men. However, he added that there is a growing awareness among some families.

He further emphasised that this could be worse when a married woman is involved because if she engages in such activities without her husband’s consent or support, it may lead to divorce.

However, with cooperative societies and women organisations springing up, there is growing awareness and support. He further called on the government to intensify awareness campaigns to make people understand that allowing women to participate in profitable farming does not mean they will lose their identities, emphasizing that religious scholars and traditional authorities also have a role to play.

This reflects the policy’s emphasis on addressing gender differences and ensuring equal opportunities in the agricultural sector as seen in Policy’s Conceptual Framework

On his part, Abubakar Usman Karfi, the chief executive officer of Silvex International, an agricultural firm in Kano and Jigawa, says it has been a norm that men tend to get bigger size farms even when inheritance is shared and due to a phenomenon he dubbed “absentee ownership.”

“Most of these women farmers don’t go to the farm themselves; they delegate men to manage the farm on their behalf, and because of that absentee ownership, they are not there themselves to manage the farm, which poses an opportunity for some of the challenges identified to thrive,” he said.

However, he is of the opinion that access to market in a technology-driven century should not be a cause for concern because with the right training, skills, access to information, pricing surveillance, and market intelligence, women can thrive. But he says unholy practices of middlemen which eliminate fair trading frameworks that regulate and guide everybody on where to buy, how to buy, and what should be the transaction dynamics lead to the shortchanging of farmers.

While calling for the full implementation of the National Policy on Gender in Agriculture by relevant stakeholders, Karfi opines that a multi-pronged approach to achieve effectiveness and address lingering issues is key.

He supports the idea of training programs that can equip women farmers with the skills they need to negotiate effectively, ensuring access to legal representation to help them defend their rights and resolve land disputes, and designing resource distribution initiatives by the government to be more inclusive, ensuring women farmers receive the support they need to thrive.

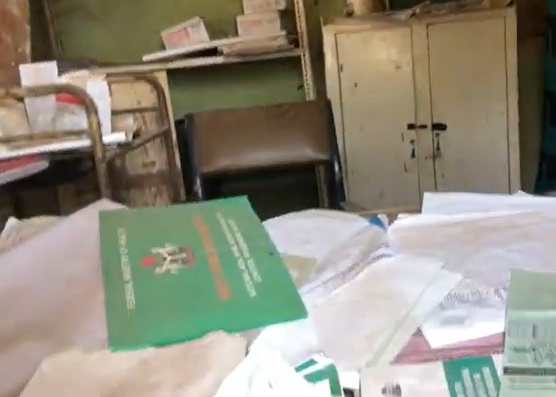

National Gender Policy in Agriculture

This aligns with the Nigerian National Gender Policy in Agriculture, as highlighted in the 2019 CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions, and Markets Annual Report. The policy aims to promote the adoption of gender-sensitive and responsive approaches in the agricultural sector, ensuring that both men and women have equal access to and control of productive resources.

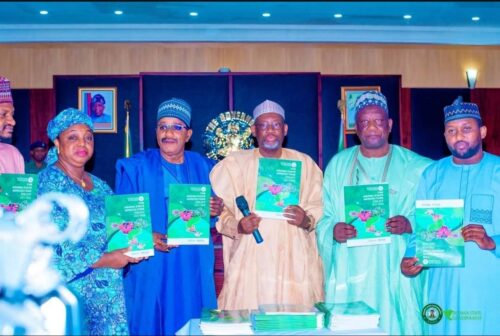

In 2019, Nigeria took a significant step towards gender equality in agriculture with the launch of the National Gender Policy in Agriculture. This policy recognises the crucial role women play in the agricultural sector, often as smallholder farmers, and aims to bridge the gap in access to resources and opportunities.

Prior to the policy, women faced numerous challenges. They often lacked access to land ownership, credit facilities, and essential tools like water pumps and storage silos. Additionally, limited negotiation skills left them vulnerable to unfair pricing for their produce. The National Gender Policy seeks to address these issues by promoting equal access to resources, training programs, and legal representation.

The policy’s ultimate goal is to empower women farmers and unlock their full potential. By fostering gender equity in agriculture, Nigeria can not only improve food security but also drive economic growth and create a more sustainable and just food system for all.

While the Jigawa State government may have made some good strides, it is still far away from consolidating the intentions of the gender policy.

When we reached out for comments concerning the efforts the state government is making to consolidate the policy in the state and address issues identified by this investigation, Muttaka Namadi, the Jigawa state commissioner for agriculture and natural resources initially gave an appointment for a meeting in Abuja on May 15, 2024. However, subsequent calls to the commissioner on the meeting were not successful as his line was not reachable.

A follow-up call was made and a text message sent to the commissioner on May 18, informing him of the presence of the reporter in Dutse, Jigawa state, having learned that he had returned to the state, but he did not reply. Similarly, on the 21st and 22nd of May, text messages with the accompanying questions for the commissioner’s attention were sent by WhatsApp and SMS, but there was no response.

This was followed by several calls on the 15th, 18th, and 22nd of May 2024, all of which went unanswered.

However, Dr. Saifullahi Umar, the Technical Adviser to the Governor on Agriculture, said that under the leadership of Governor Umar Namadi, Jigawa State has taken a targeted approach to empower women farmers, aligning with the National Gender Policy on Agriculture to meet the specific needs of women in the region. He further highlighted the administration’s efforts since taking office in August 2023 to prioritize agricultural development with a strong focus on gender inclusivity.

He explained that Jigawa State has adapted the National Gender Policy on Agriculture to suit its unique local context, ensuring that women are integral to every aspect of agricultural development. He said the government has achieved a 50% inclusion rate for women through the NG-CARES FADAMA initiative, which focuses on supporting women and youth from vulnerable and high-risk communities by providing essential agricultural assets, inputs, services, and capacity-building opportunities.

“The FADAMA initiative is central to Jigawa State’s strategy to empower women in agriculture.

Nearly 40,000 women and youth have benefited from the program, engaging in various agricultural enterprises, including rice, sorghum, millet, and maize production, as well as goat livestock farming. The government equips these beneficiaries with essential agricultural tools and training, enhancing productivity and income”.

Dr. Umar emphasized the government’s commitment to addressing challenges such as land encroachment and gender-based discrimination.

To protect women’s land rights and ensure equitable access to resources, he said that the government has implemented specific measures, including legal support and collaboration with local authorities to enforce land rights and reduce disputes.

To improve market access and infrastructure for women farmers, the government is enhancing transportation networks and storage facilities, he stated.

Dr. Umar conceded that access to markets and efficient transportation are significant barriers for women farmers and noted that by improving the road networks and providing processing equipment, the government enables women to bring their produce to market more effectively, add value to their products, and increase their income.

Security and safety are also key priorities, Dr. Umar said, stressing the importance of creating a safer environment for women in agriculture. He said that the government is working with local security agencies to protect women farmers from harassment, theft, and crop destruction, particularly in rural areas. Perpetrators of such unlawful acts will face strict legal consequences.

Recognizing additional challenges faced by women, such as limited access to premium seedlings and agricultural technology, the government, he stated, has launched initiatives to improve access to quality inputs. Programs have been established to provide women farmers with necessary agricultural inputs and offer training and capacity-building sessions to enhance their farming practices. The aim is to empower women farmers to be resilient and self-sufficient, significantly contributing to the state’s agricultural output.

One notable program is the Rice Millennial Program, which has empowered 1,000 youth, including young women, to produce rice seeds. This initiative highlights the potential for financial independence through rice cultivation.

Moreover, the state has strengthened its agricultural extension services by recruiting 1,435 extension agents and 300 community animal health workers to operate mobile veterinary clinics. This initiative ensures that women farmers receive timely advice and support on best farming practices and animal health.

Dr. Umar observed that Jigawa State’s focus on women farmers represents a comprehensive approach to agricultural development, ensuring inclusivity and sustainability. By addressing gender-specific challenges and providing the necessary support and resources, the government is paving the way for a more inclusive and resilient agricultural sector, he said further.

He concluded by reaffirming the government’s commitment to fostering an inclusive agricultural sector that supports both men and women farmers, aiming for sustainable growth and food security in Jigawa State.

However, analysists say it remains to be seen how the Jigawa State government and stakeholders at all levels will embrace the National Gender Policy on Agriculture, address challenges which can empower women farmers, promote agricultural development, and create a more equitable food system for all.

To truly empower women farmers in Jigawa and across Nigeria, some say there’s need for implementation of the National Policy on Gender in Agriculture in full. This requires concerted efforts from government institutions, development partners, civil society organizations, and the private sector to address the specific challenges faced by women farmers.

This report is produced with support from the International Center for Investigative Reporting (ICIR).